A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective

“A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective” compares Phase One with Phase Two, and describes what is proposed for Phase Three. Design features to be reviewed include the walk system, seat furnishings, plantings, signage and graphics, water feature and drinking fountains, public art, lighting, maintenance and irrigation, and Phase 3. The author also offers suggestions on economic impacts, restrictions and user activities, sustainability, and studies/research.

Originally, due to the length and photo essay nature of the contribution, the series was presented approximately every few weeks in 14 parts between 2013 and 2015; to ensure background information, the Series Introduction is repeated on all.

Part 9 – Proposed Phase Three

By Steven L. Cantor, Landscape Architect – Originally Posted June 3, 2014

All Photos © Steven L. Cantor Unless Otherwise Noted

Series Introduction

Phase One High Line on July 15, 2009.

Designed by landscape architect James Corner of Field Operations, architect Ricardo Scofidio of Diller Scofidio + Renfro with planting design by Piet Oudolf, the High Line, the remarkable linear park built on an abandoned railroad viaduct in New York City, has been enormously popular.

The design team anticipated how well green roof technology would function and adapt to the viaduct since it could handle at once the huge weight of several fully-loaded trains carrying heavy tonnage. As an intensive green roof, it has very few structural load limits which would curtail use. At peak use times there can be lines of pedestrians waiting to enter with as many as 20,000 visitors per day on weekends.[1]

The High Line has won numerous awards, and in particular several as a green roof, for example, in 2013 and 2010 from the American Society of Landscape Architects, Green Roofs for Healthy Cities in 2011, and in 2010 from the International Green Roof Association. This is a rare public project in which the success of the initial phase contributed to a high level of funding for subsequent phases.

7.16.11.

The High Line has benefited from intense scrutiny as a result of lectures in which the designers were questioned; public hearings, media critiques in newspapers, journals, and blogs; lobbying from specific organizations, such as the Rainforest Coalition; and comments from city government and other public officials.

Improvements or adjustments were implemented to some design elements of the first phase, and significant modifications were done in the second phase. Are these changes aesthetic, appropriate and ethical, and are they consistent with the goals of sustainability? Is the High Line a sustainable design?

Part 9: Proposed Phase Three Discussion

Aerial graphic of the Spur looking west. The new design concept for the High Line at the Rail Yards includes an immersive bowl-shaped structure on the Spur, a section of the High Line that extends over 10th Avenue at West 30th Street. Image by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, courtesy of the City of New York with permission of Friends of the High Line.

Also known as The High Line at the Rail Yards, Phase Three is the final section of the High Line (the first phase of which opened in September, 2009) and is expected to be completed in late 2014 or perhaps early in 2015.

A view along current northern end of Phase Two of the High Line, with a structural column for 10 Hudson Yards in the background on 1.12.14.

Same view as above about four months later on 5.18.14.

On July 30, 2012 I attended a public presentation at the High Line itself (set up within the shadow of one of the buildings that bridges over the park) on the design for the proposed Phase Three. My descriptions herein are based on this lecture and updates that have appeared on the High Line website and the Hudson Yards website.

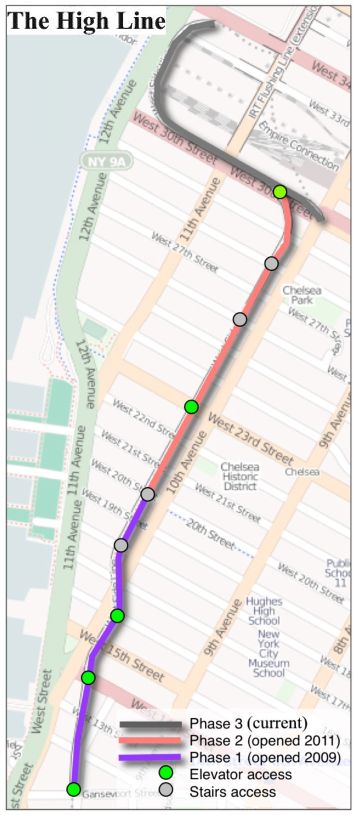

Map of the High Line in Manhattan, New York City. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Original image Anders Thorseth. Updated by user: PeterEastern and Linda S. Velazquez.

View of the north end of the High Line as it approaches W. 30th Street. 3.15.14.

Starting at the north end of the 30th Street Cutout and the Viewing Platform (the northern end of Phase Two), the High Line forms an angled T intersection.

Hudson Yards Master Site Plan. Image courtesy ©Related-Oxford.

A short segment (called the Spur) will turn sharply east and connect with the existing federal post office building, which may become the new central train station. But the main route of the High Line will angle westward, in the opposite leg of the “T” and proceed towards the Hudson River as far as 12th Avenue, wrap around the Hudson Yards, a vast new urban design being developed over the rail yards. At 12th Avenue, the High Line will turn north until 34th Street, where it will ramp down eastward to be flush with the street and link to the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center.

Looking north on the High Line, with 10 Hudson Yards skyscraper under construction in the background; it will eventually be 895 feet tall or 52 stories, and encompass 1,700,000 square feet. 5.12.14.

10 Hudson Yards, High-Line Entrance. Image courtesy ©Related-Oxford.

Much of the Hudson Yards is still in design development, yet the two projects will be fully integrated, so it is likely that there could be additional links between the High Line and plazas and entrances for the massive buildings being proposed. A new subway link and station for the 7 line will be incorporated in Hudson Yards, along with considerable public open space.

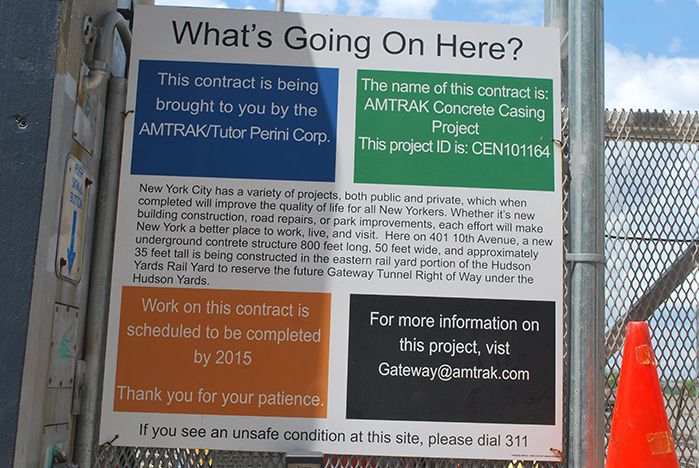

A view from 10th Avenue near W. 31st Street of the MTA (Metropolitan Transportation Authority) and LIRR (Long Island Rail Road) West Side Storage Yard Complex. In the left background are the lower stories of 10 Hudson Yards under construction. 5.18.14.

Close-up of signage at Storage Yard. 5.18.14.

10 Hudson Yards, the first tall skyscraper, is under construction at the northwest intersection of 10th Avenue and West 30th Street. Immediately adjacent to the current location of the 30th Street Cutout and Viewing Platform on the High Line, this first Hudson Yards building will rise 52 stories to a height of 895 feet.

A view looking west along West 30th Street, with end of Phase 2 of High Line in the background, and the construction of 10 Hudson Yards to the right. 3.15.14.

Elevator at northern end of Phase Two of the High Line at West 30th Street.

10 Hudson Yards is under construction across West 30th Street. 5.12.14.

Eventually, a complex of skyscrapers and open space will be arranged north and west of this new building. For example, 30 Hudson Yards, at the southwest corner of 10th Avenue and West 33rd Street, will tower 80 stories to a height of 1,227 feet and be the fourth highest building in Manhattan (about 549 feet beneath the height of the new Freedom Tower in lower Manhattan).

10 and 30 Hudson Yards with retail, looking northeast. Image courtesy ©Related-Oxford.

30 Hudson Yards and retail, viewed from 33rd St and 10th Ave.

Image courtesy ©Related-Oxford.

On October 17 of last year at the 2013 Municipal Art Society’s Summit in New York City, landscape architect James Corner of James Corner Field Operations, architect Matthew Johnson of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, city councilman-elect Corey Johnson, and the co-founders of the High Line Joshua David and Robert Hammond presented more recent concepts of the dramatic climax to the High Line.[8] The dominant feature at 10th Avenue and West 30th Street will be an intimate, floating garden, dubbed as “the bowl.”

The Spur, aerial view looking west: A bowl-shaped structure will mark this northeast terminus of the High Line at 10th Avenue and 30th Street, creating an extraordinary, sheltered, and vegetated interior room that one discovers through various openings and entries. This aerial view of the Spur looks west toward the Hudson River. Image by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, courtesy of the City of New York with permission of Friends of the High Line.

This “bowl” will be constructed over the “Spur,” a route extending eastward from the current northern terminus of the High Line towards the main United States Post Office, which eventually may become the city’s new rail terminal, replacing the current Penn Station. (The main route westward towards the Hudson is described below.)

A view of the United States Post Office at 9th Avenue/ West 30th Street. 3.15.14.

Also called “the nest,” this proposed bowl-like feature will float above the intersection, simulating some giant futuristic bird’s habitat, but will be populated by pedestrians and plant materials at various levels above the promenade. Snakeback maple and black tupelo are proposed trees to screen the view of the Hudson Yards development and frame views of vibrant new urban design. When completed in 2016, there will be a direct pedestrian link to the southern and southeastern section of the Hudson Yards.

The design will include zinc-clad structures incorporating tiered seating and additional restrooms. The trees will be underplanted with the diverse vocabulary of groundcovers, ferns, grasses and shrubs that have been such a successful part of previous phases.

The Spur, looking east along West 30th Street: Approaching the exterior of the bowl structure from the west, at West 30th Street and 10th Avenue. Tiered seating along the outside perimeter of the bowl provides impressive views of the surrounding city and Hudson River. The structure also provides much-needed work space and amenities, such as public restrooms. Image by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, courtesy of the City of New York with permission of Friends of the High Line.

The design vocabulary will be similar to previous phases of the High Line, with several innovations. Starting near 10th Avenue, a combination of pavements integrated with rails and naturalistic plantings will continue. Farther west a grasslands landscape, highlighted with a grove of honey locust trees, is proposed.

The designers are introducing a new bench vocabulary: a rocking style bench, a conversation bench, and a xylophone bench, the designs for which are still being developed. Adjustable umbrellas will be provided in the most open areas for shade. There will be clear sight lines to the river, and the pavements will at times be elevated over the existing grade of the trestle to give more dramatic views.

“The Spur, interior of the bowl, looking east: stepped seating lines the base of the structure, ringed with broad-leaf woodland grasses, perennials and ferns. Snakebark maple and black tupelo trees frame views to the sky and towers above. Bowl interior view in the fall, looking east,” (High Line). Image by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, courtesy of the City of New York with permission of Friends of the High Line.

Another distinct feature will be a children’s playground is being proposed in the area bridging over 11th Avenue, and will feature sensory gardens, views of the infrastructure, water fountains and restrooms, and some elements reminiscent of an adventure playground, like a simulation of a gopher hole, which is typically part of a prairie landscape.

“The Spur, interior of the bowl, looking west: in contrast to the surrounding urban development, the bowl structure provides a lush and otherworldly environment inspired by the dense layers of a woodland habitat, immersing visitors in nature. Bowl interior view, looking west,” (High Line). Image by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, courtesy of the City of New York with permission of Friends of the High Line.

After this unusual activity, the High Line will gradually slope down towards the river and reach the approximate street grade at 12th Avenue. The High Line will curve northward near the intersection of 12th Avenue and West 30th Street, go parallel to 12th Avenue for about four blocks and then move eastward on West 34th Street to terminate at the convention center. This design is still being developed.

The High Line’s website (www.thehighline.org) features a remarkable video (prepared in 2008) showing the step by step implementation of the High Line from Gansevoort Street northward. Little is shown of the third phase, but perhaps as the design progresses, the organization and design team will expand the video. It is somewhat difficult to appreciate the proposed design of Phase Three because most of it is described with specific, beautifully rendered graphic images but not a continuous sequence of spaces drawn on a map against the street grid and made available as a plan for public review and comment.

At the presentation which I attended almost two years ago, questions and comments were solicited from the audience by the design team representatives. Perhaps, this process is continuing at public forums throughout Chelsea until the design is finalized. On July 30, 2012 I made three suggestions via note cards which interested members of the audience such as myself could turn in to High Line representatives at the conclusion of the presentation:

- To consider another species of trees besides honey locusts, as there are several adaptable species that are much more distinctive, such as Pagoda Tree, Sophora japonica, and many others; just as one example, three leaf maples, Acer tripetalum, have adapted well at the Tenth Avenue Square. Perhaps, the design team would prefer a different, unusual species so will not want to repeat one. However, for a planting design as imaginative as the High Line’s it seems inappropriate to use honey locust, as ubiquitous as weeds.

- To coordinate the design and construction of the playground with the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation as there are so many safety issues and other stringent requirements about materials, dimensions, finishes that can be easily overlooked when new elements are being designed, rather than incorporating established manufacturers’ standard equipment or furnishings. The more common method is for designers to incorporate and specify well-established manufacturers’ standard equipment or furnishings in order to avoid liability issues. It will be indeed be a remarkable achievement to enjoy an adventure playground if the High Line design team can overcome this obstacle.

- And to consider using composting toilets, such as Clivus Multrums, since they would be both educational and minimize the challenges of bringing infrastructure connections to this particular location. In the new public rest room at the High Line’s headquarters near Gansevoort Street, toilets are incorporated which greatly reduce water usage. So, to incorporate another example of an environmentally friendly toilet system would reinforce this message.

I assume that the final Phase Three design will continually be redeveloped, tested and implemented in a careful and precise manner. It will be enlightening to see the final design, and experience the degree and extent to which the design team is successful in creating one continuous and magical experience for pedestrians from Gansevoort Street to West 34th Street.

5.10.12.

Additional High Line Phase Three Photos

That’s it for now. I hope that these different sections of text and images of the High Line will generate discussion.

Come back next time for Part 10 of “A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective” where I’ll discuss Economic Impacts.

Steven L. Cantor

Photos © Steven L. Cantor are available for individual purchase.

Cumulative 14-part “A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective” Series End-notes

1. Ulam, Alex. “Back on Track,” Landscape Architecture Magazine. Volume 99, No. 10, October, 2009, p. 97.

2. http://www.thehighline.org/news/2012/01/24/major-milestone-for-the-high-line-at-the-rail-yards

3. http://www.thehighline.org/sustainability

4. http://www.thehighline.org/design/planting

5. Ulam, Alex. “Back on Track,” Landscape Architecture Magazine. Volume 99, No. 10, October, 2009, p. 97 and 105-106. He refers to an article in the New York Post.

6. David, Joshua, Reclaiming the High Line, a project of the Design Trust for Public Space with Friends of the High Line. Karen Hock, editor, (New York, Ivy Hill Corporation and others, 2002). p.7.

7. http://www.thehighline.org/about/ask-a-gardener

8. http://untappedcities.com/2013/10/17/live-blog-from-2013-mas-summit-for-nyc-day-1/

http://untappedcities.com/2012/04/26/partners-in-preservation-the-high-line-section-3/

http://untappedcities.com/2013/11/13/spur-the-third-section-of-the-high-lines-crown-jewel-a-nest-in-the-sky/ (by Bhushan Mondkar)

Publisher’s Note:

See Steven L. Cantor’s ENTIRE 14-part “A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective” Series.

Steven L. Cantor, Landscape Architect

Photo by Thomas Riis.

Steven L. Cantor is a registered Landscape Architect in New York and Georgia with a Master’s degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He first became interested in landscape architecture while earning a BA at Columbia College (NYC) as a music major. He was a professor at the School of Environmental Design, University of Georgia, Athens, teaching a range of courses in design and construction in both the undergraduate and graduate programs. During a period when he earned a Master’s Degree in Piano in accompanying, he was also a visiting professor at the College of Environmental Design at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He has also taught periodically at the New York Botanical Garden (Bronx) and was a visiting professor at Anhalt University, Bernberg, Germany.

He has worked for over three decades in private practice with firms in Atlanta, GA and New York City, NY, on a diverse range of private development and public works projects throughout the eastern United States: parks, streetscapes, historic preservation applications, residential estates, public housing, industrial parks, environmental impact assessment, parkways, cemeteries, roof gardens, institutions, playgrounds, and many others.

Steven has written widely about landscape architecture practice, including two books that survey projects: Innovative Design Solutions in Landscape Architecture and Contemporary Trends in Landscape Architecture (Van Nostrand Reinhold, John Wiley & Sons, 1997). His book Green Roofs in Sustainable Landscape Design (WW Norton, 2008), provides definitions of the types of green roofs and sustainable design, studies European models, and focuses on detailed case studies of diverse green roof projects throughout North America. In 2010 the green roofs book was one of thirty-five nominees for the 11th annual literature award by the international membership of The Council on Botanical & Horticultural Libraries for its “outstanding contribution to the literature of horticulture or botany.”

Steven’s most recent book is Professional and Practical Considerations for Landscape Design (Oxford University Press, 2020) where he explains the field of landscape architecture, outlining with authority how to turn drawings of designs into creative, purposeful, and striking landscapes and landforms in today’s world.

He has been a regular attendee and contributor at various ASLA, green roofs and other conferences in landscape architecture topics.

In recent years Steven has had more time for music activities, as a solo pianist and accompanist. In 2011 he performed a solo piano program at the Winter Rhythms festival at Urban Stages Theater. He’s a regular performer at musicales hosted in Chelsea and other settings in Manhattan. On August 25, 2013, Leonard Bernstein’s birthday, he performed with Stephen Kennedy Murphy a program of excerpts from the composer’s MASS and Anniversaries.

Steven joined the Greenroofs.com editorial team in December, 2013 as the Landscape Editor. In February, 2015 he completed his 14-part series “A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective.”

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture