Staff of Climate Central writes:

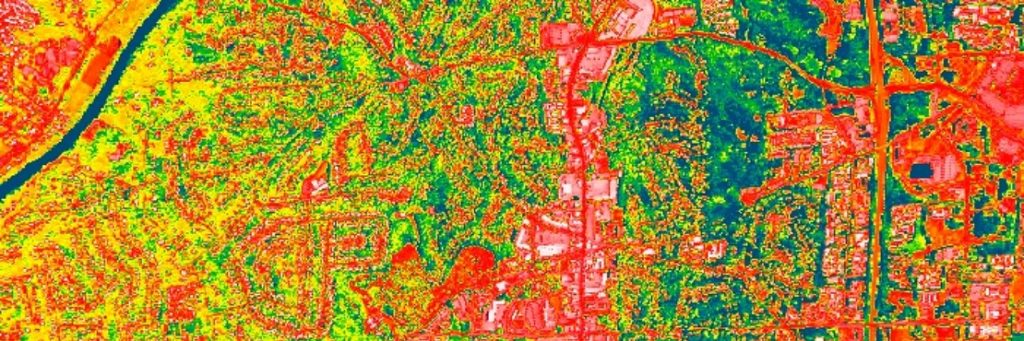

Urban heat islands are metropolitan places that are hotter than their outlying areas, with the impacts felt most during summer months. About 85% of the U.S. population lives in metropolitan areas. Paved roads, parking lots, and buildings absorb and retain heat during the day and radiate that heat back into the surrounding air. Neighborhoods in a highly-developed city can experience mid-afternoon temperatures that are 15°F to 20°F hotter than nearby tree-lined communities or rural areas with fewer people and buildings.

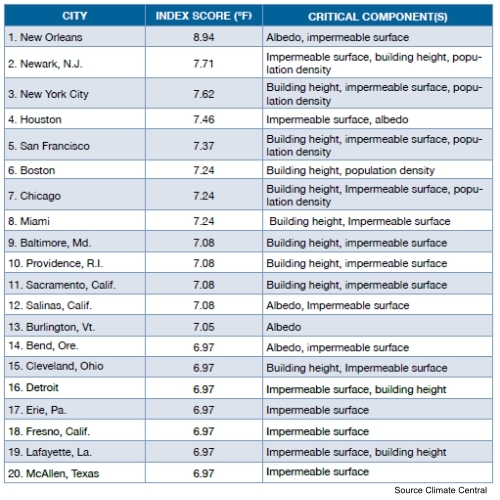

Climate Central, an independent organization that researches climate change, released a report on July 14 that ranks 159 US cities by their urban heat intensity index. The study refers to these cities as “urban heat islands.”

Each city was given an index score which represents the average temperature difference between the city and what the heat may have been in that location if not an urban area.

This score was primarily based on – in order of consideration – albedo (the reflectivity of the surfaces in the city, such as rooftops and roads), percentage of greenery, population density, building height, and average street width and city irregularities.

Climate change is making extreme heat events worse and more frequent, with summer temperatures stretching into the shoulder seasons of spring and fall. Heat events adversely affect health and quality of life—and this is especially acute in urban communities. Higher cooling demand strains the electric grid and raises electric bills. And heat-related impacts fall unequally, with historically underserved populations facing greater health threats.

This report looks at the factors that contribute to the heat island effect, and analysis that will show how they vary in places across the United States. Discussions of some of the impacts of higher temperatures on human health and the built environment is described. Also, a look is provided at how communities are adapting to these new normals with considerations to solutions for lessening some of the intensity of the urban heat island.

This report looks at the factors that contribute to the heat island effect, and analysis that will show how they vary in places across the United States. Discussions of some of the impacts of higher temperatures on human health and the built environment is described. Also, a look is provided at how communities are adapting to these new normals with considerations to solutions for lessening some of the intensity of the urban heat island.

Longer-term solutions are often more difficult in terms of planning and finding adequate resources and funding, and not all mitigation strategies work for all places:

- Planting trees, particularly along paved streets. Shaded surfaces may be 20–45°F (11–25°C) cooler than the peak temperatures of unshaded surfaces. Trees also absorb carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas), improve air quality, and can slow down stormwater runoff. American Forests have created an interactive tool to look at “tree equity” at the local level.

- A green roof, or rooftop garden, is a vegetative layer grown on a rooftop and can provide shade and lower temperatures of the roof surface and surrounding air. There are a number of examples around the country. Check out the gardens on the roofs of Chicago’s and Atlanta’s city halls, the meadow atop the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens Visitor Center, and the nearly 10,000 square foot American Society of Landscape Architects Headquarters in Washington, D.C., which is home to nearly 5 million square feet of green roofs.

- Cool roofs are made of highly reflective and emissive materials that remain cooler than traditional materials, and help to reduce energy use.

- Cool pavements, or whitewashing roads and sidewalks, is more complicated than roofs. In cities with urban canyons, the sunlight may not even reach the street level long enough to make a significant difference. In places like Los Angeles, a cool pavement study showed that heat was reflected off the white surface, but onto pedestrians and made people feel hotter.

- While research has shown that the width of streets, canyon orientation and building heights all have a role in urban heat island, varying the height of new buildings to increase air circulation and considering the layout of streets and buildings is a holistic but much more long-term approach for cities and planners.

- ACEEE maintains a database tracking mitigation efforts for urban heat islands across most major U.S. cities.

- In 2020, solar power was the cheapest source of electricity in many parts of the world. By displacing fossil fuel-based electricity, solar energy can reduce not only carbon dioxide emissions but also reduce air pollutants that are a threat to public health. Solar panels have also been shown to provide shade and reduce the heat island effect. There are a number of equitable strategies to deploy solar energy, allowing disadvantaged communities to see significant co-benefits such as reduced energy bills and good jobs.

https://youtu.be/nX_nnf996jE

Read more: Hot Zones: Urban Heat Islands

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture