A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island, Part 1 of 3

Images by MNLA are noted; all others are by ©Steven L. Cantor

Image: MNLA

NARRATIVE AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION

Concept: Principal of MNLA (Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects), Signe Nielsen describes her concept for Little Island, the fanciful 2.4-acre park appearing to float like a magical green carpet above the eastern edge of the Hudson River by New York City’s Pier 54 and 56, “as a leaf with upturned edges.”[1]

Little Island South Bridge entrance. Image: MNLA

The concept gives way to the reality of a remarkable construction raised up to a height of well over 60 feet above the Hudson River on a system of columns. Except for birds and passengers in planes, perhaps no one experiencing it would realize that the island is a perfect square shape, 320 feet per side. An abundance of topographic variation allows for diverse plantings including trees of dramatic heights, underlain by unusual textures of shrubs and groundcovers: the frothy edges of vines and grasses, for example.

Arrival: From a grand arrival plaza by the Hudson River Esplanade (adjacent to the West Side Highway), which includes the renovated archway from the original piers, are two contrasting means of entry for Little Island pedestrians.[2]

South Bridge of Little Island with the renovated archway at the Westside Highway in the background

Image: MNLA, © Elizabeth Felicella

South Bridge entering Little Island. Image: MNLA

One option is a straight, processional route along the South Bridge from West 13th Street, leading directly under the giant magic mushroom shapes of the island’s infrastructure. This route also functions as emergency access, providing clearance for fire trucks underneath a graceful arch.

Visitors arriving from the South Bridge. Image: MNLA, © Elizabeth Felicella

Arrival Plaza

North Bridge entrance

Corner at the North Bridge entrance with South Bridge in background

The alternate route is a slower passage along a narrower North Bridge aligned with West 14th Street, which makes a sharp 90 degree turn to the left and enters a totally different parkland from the urban environment from which one has just departed. Both entries ascend gently towards the island from the paved plaza, as if one is starting a journey towards grace.

Arrival Plaza at Little Island

South Bridge entrance from arrival plaza near West 13th Street

Signe Nielsen indicates that she was inspired by the gentle gradient of the pavements of the Channel Gardens at Rockefeller Center. This is typical of the processional gradient of many traditional Japanese and Chinese gardens, in which a steady but unrelenting gradient creates a sense of expectation.[3] She explains that further reasons for the upward slopes on the two bridges and the upturned southeast and southwest corners is twofold: to lift the park above the flood zone/ sea level rise and also to allow sunlight to penetrate deep underneath the pier for marine habitat.

North Bridge Pier and ruins of Pier 56

South Bridge

North Bridge overlooking ruins of Pier 56

Comparison to the High Line: Since the Gansevoort Street entrance to the High Line — the spectacular 1.45-mile-long green roof which extends all the way to West 34th Street — is only about a five-minute walk to the 13th Street entrance to Little Island, some comparisons are appropriate.

Beginning of the High Line at Gansevoort Street

Walking south on the High Line near its famous sheet-flow water feature and portable benches (the Diller -Von Furstenberg Sundeck and Water Feature), an observant person can glimpse Little Island, with the tightly linked toadstools holding up the sky, yet the histories of these two projects are somewhat different.

The Diller -Von Furstenberg Sundeck and Water Feature

After long planning efforts, the first three phases of the High Line were built and opened over a period of about a decade starting in 2009 for a cost of about $229 million. New York State’s Governor Kathy Hochul earlier this year announced an extension to connect to the Moynihan Train Station (the former Post Office) for $50 million[4], and there is planning underway for an extension for another $60 million to link from the Javits Center to Hudson River Park. The grand total is about $340 million from public and private funds.

Parallel to these costs, of course, are the well-publicized, negative as well as positive impacts, of many businesses and residents being forced out by rising rents, demolitions, and gentrifications. Huge increases in tourist revenue and the creation of many new businesses have also occurred. The High Line can perhaps be thought of as a benevolent boa constrictor constantly growing and expanding through various neighborhoods, linking them while digesting them. At the same time there is no doubt that the High Line is a horticultural wonderland, a display venue for art and sculpture and a social mecca. Its skilled design team has had the advantage of studying each phase of work carefully, revising and refining details in subsequent phases to keep improving upon the results of earlier efforts.

By contrast Little Island took four years to plan and three years to build.[5] All of the plantings were installed from March to October, 2020. The total cost was $250 million, all but $17 million of which was provided by the Diller von Furstenberg Family Trust; the former sum was paid for by Hudson River Park Trust.[6]

“What was in my mind,” Diller described, “was to build something for the people of New York and for anyone who visits—a space that on first sight was dazzling and upon use made people happy.”[7]

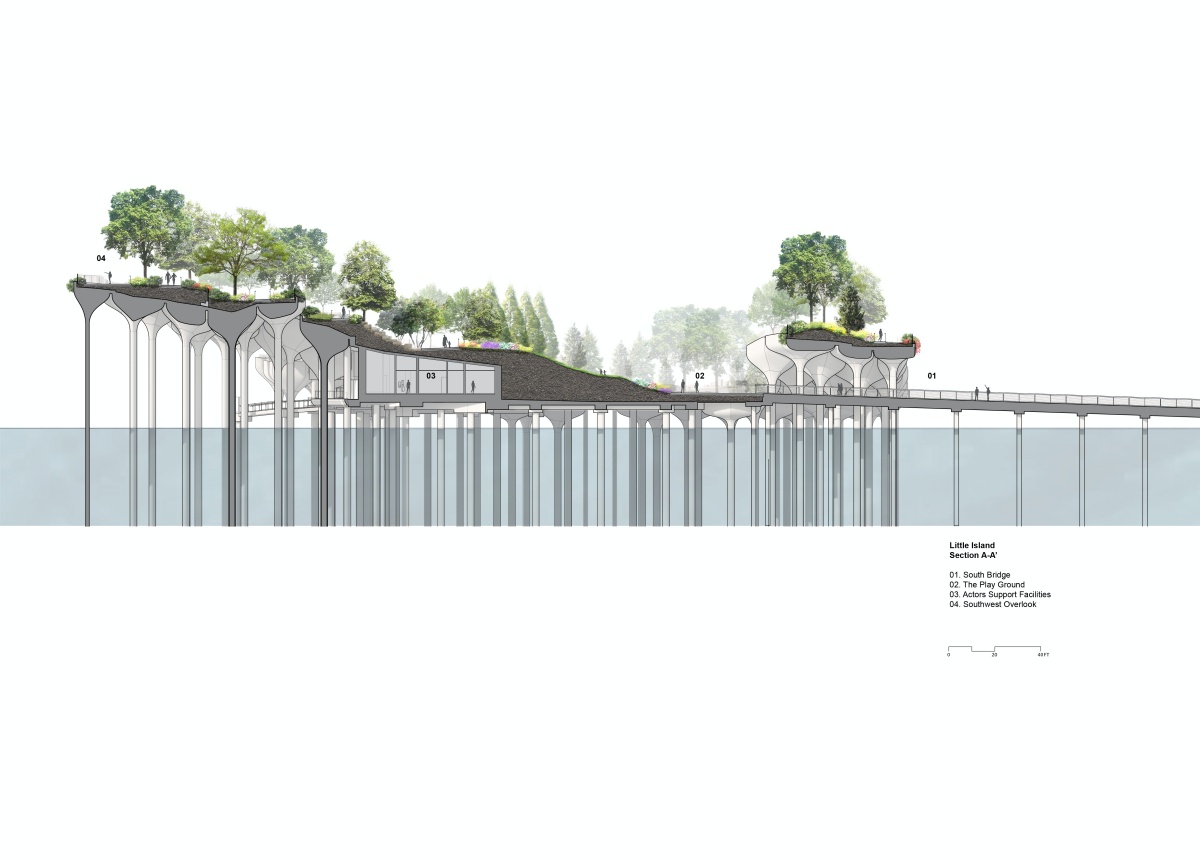

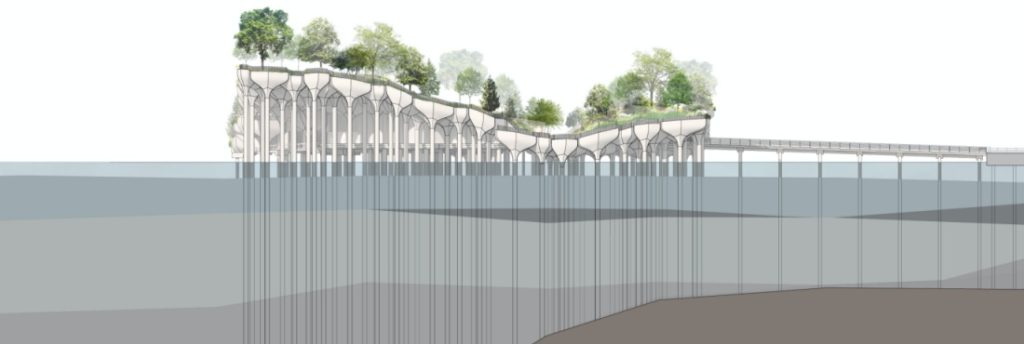

The island as a green roof: The highly complex construction is an intensive green roof, using various techniques to climb to a height of 62 feet over the Hudson River. There are minimal impacts on adjacent buildings or properties.

Little Island Section A-A’. Image: MNLA

Signe Nielsen explained:

“Soil depths range from 24 inches to 6 feet (at hero tree* locations) because the soil profile and the concrete slab are not parallel; the depth of soil is a direct function of the loads that can be sustained on the piles, so where we needed to build up the finished grade, we used drainage mat, drainage gravel, and geofoam below the soil. Not all the areas have geofoam under them so in the shallower depths, for the most part, there is only drainage mat (gravel, filter fabric) and soil.”[8] ~ Signe Nielsen

* Hero Trees are defined next time in Part 2 in the section which follows on planting, but are essentially specimen trees with large root balls.

Because the Little Island program was so diverse and the construction challenges so complex, there were crucial and ongoing collaborations with a diverse group of consultants. The following paragraphs will briefly describe the overall design and planting, and then will provide some level of detail about the green roof design.

Overall layout: One can imagine the Little Island park as three hills grouped around an irregular lawn. Another way is to envision four quadrants, the northeast of which is paved and used as a multi-purpose food court, playground[9] and gathering area, which I will refer to from hereon as the plaza, while the other three quadrants encompass landforms which feature hilltops. Based on its orientation and topography each quadrant has its own microclimate and landscape preferences.

To the northwest is a rolling landscape modeled after the coastal bluffs of Acadia National Park. Remarkably, the topography climbs and conceals a 700-seat amphitheater, the AMPH, carved into the far corner of the site. The stage is only about 10 feet above the level of the river while the highpoint of the surrounding gardens and plantings is a spectacular lookout point, near a standing room only railing, 37.5 feet above the river, offering panoramic views over the Hudson and the skeletal remnants of the old piles of Pier 56. Because the exposure of this quadrant tends to be to the south with a lot of intense sunlight, the landscape is planted with materials whose foliage, blooms or berries are intense colors that will not wash out.

Lawn looking southeast

Lawn and steps adjacent to the steel sheet pilings performing as retaining walls

Amphitheater, the AMPH

To the southwest is the highest point of the park, a much more spacious lookout platform at an elevation of 62 feet above the river with a totally different prospect offering different views over grandly expansive reaches of the Hudson River, the distant harbor and New Jersey. To reach this height the visitor chooses between unique options: either meandering up a gracefully aligned walkway compliant with the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) with a pebble concrete finish or, for the more physically adventurous, climbing up a series of quartzite boulders, called scrambles, laid out perpendicular to these walks.

Amphitheater looking south

The intersections with the walks occur at the Little Island stair landings between the sections of ascending gradient. Based on its orientation, this area is more shaded and is developed as a woodland with majestic shade trees underplanted with masses of shrubs and groundcovers, including ubiquitous grasses. About halfway up the walkway system, visitors are afforded engaging views of the officially designated tulip pot system (rather than mushrooms), connected to structural piers that support them and carry the weight of the entire island.

View of South Bridge under tulip pots

Entry to the restrooms

Underneath this massive hill is a cavelike space in which spacious restrooms are provided, accessed from the walk from the far southern end of the plaza. The entrance to the restrooms is adjacent to the Glade, a secluded but sunny space for small gatherings and performances. It should be pointed out that there are also sets of stairs to this southwest high point (and the other two high points on the island), gracefully inserted into the landform. The sheer mass of the stairs is artfully disguised by the luxuriant plantings. Another technique used to downplay the scale and height of these stairs is the interlocking wood detailing, as well as the use of a palette of restrained colors blending with the landscape.

The Glade

The steps, steel sheet piles and the plantings are in tandem

“White Garden”

S-shaped walk

In the southeast quadrant are located two contrasting gardens, a white garden nestled into a hidden space that pedestrians discover after they have climbed up through another system of ADA compliant paths, stairs and boulder scrambles planted as a garden theme with yellow, lime-green and purple foliaged or blooming materials. The curving walks unfold alternate views into the park or towards the city. A substantial sloping lawn area for sunbathing also offers views back towards the city or interior areas of the park, including the Whitney Museum of Art (next to the entrance of the High Line) as well as for sitting to look towards the Glade. One consistent aspect of Little Island’s design is the variable views visitors experience as they walk, from looking out towards the city or the river alternating with views inward towards intimate views of the park itself.

View of the exit to the South Bridge

Southeast hill adjacent to Plaza and food court

Lawn looking north

Plaza and food court

Little Island’s northeast quadrant encloses the plaza, and both visually and acoustically screens it from the Hudson River Park Esplanade and the Westside Highway. Significant plantings of evergreen trees and shrubs do the screening. The plaza, at an elevation of 16 feet above the river, is paved with circular patterns of unit blocks of square Hanover Prest Brick (concrete pavers with tumbled finish), accented and contrasted with whimsical double rows of dark Volkanite™ (manufactured in England) of cast basalt[10] that appear almost like schools of fish. This juxtaposition was brought about by Diller’s critique of earlier designs, which he found too dull and not playful enough.

The rolling lawn is the anchor around which the other quadrants rotate. It is centered about 16 feet in elevation above the river, which is 2.5 feet above its highest flood stage, and climbs to as high as 35 feet. This lawn is a popular space for sitting, watching people and sunbathing. The species of grass planted is a basic sun mix of 3 to 4 types of fescues and a little Kentucky Bluegrass exceptionally resilient to wear-and-tear so that it can withstand a great deal of pedestrian usage. For many visitors the lawn becomes the foreground for views upwards into the park’s magical landscapes in almost any direction. The lawn abuts the edges of the plaza and the other quadrants and creates an organic whole, in the way that mortar binds the elements of a masonry wall together.

Little Island lawn plantings; the steps are sweeping up the slopes

The following Little Island discussion provides more detail[11]; join me next time for Part 2 of 3.

Publisher’s Notes:

See Part 2 of 3.

See Part 3 of 3.

See the Little Island Project Profile in the Greenroofs.com Projects Database.

Image: MNLA

Cumulative 3-part “A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island by MNLA, Heatherwick Studio, Arup & others” Series End-notes

[2] Based on interviews with Signe Nielsen, the author follows the geographic organization of the delightful and informative audio tour by Robert Westfield at www.littleisland.org.

[3] Mitchell Bring and Josse Wayembergh, Japanese Gardens Design and Meaning. (New York, McGraw Hill, 1981), p.159, fig. 13.12

[4] https://gothamist.com/arts-entertainment/cuomos-50-million-high-line-extension-still-happening-hochul-confirms

[5] Zoom interview with Signe Nielsen October 25, 2021

[6] Email with Signe Nielsen November 16, 2021

[8] Email with Signe Nielsen May, 2021

[9] It is officially called the Play Ground but it has been causing disappointment among visitors searching for a traditional playground with equipment, so it is best to refer to it how it is designed and used, as a plaza.

[10] Email with Signe Nielsen November 16, 2021

[11] Most of this section is based on a Zoom interview with Signe Nielsen on December 6, 2021. Unless otherwise noted, quotations from her are from that interview.

Steven L. Cantor, Landscape Architect

Photo by Thomas Riis

Steven L. Cantor is a registered Landscape Architect in New York and Georgia with a Master’s degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He first became interested in landscape architecture while earning a BA at Columbia College (NYC) as a music major. He was a professor at the School of Environmental Design, University of Georgia, Athens, teaching a range of courses in design and construction in both the undergraduate and graduate programs. During a period when he earned a Master’s Degree in Piano in accompanying, he was also a visiting professor at the College of Environmental Design at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He has also taught periodically at the New York Botanical Garden (Bronx) and was a visiting professor at Anhalt University, Bernberg, Germany.

He has worked for over four decades in private practice with firms in Atlanta, GA and New York City, NY, on a diverse range of private development and public works projects throughout the eastern United States: parks, streetscapes, historic preservation applications, residential estates, public housing, industrial parks, environmental impact assessment, parkways, cemeteries, roof gardens, institutions, playgrounds, and many others.

Steven has written widely about landscape architecture practice, including two books that survey projects: Innovative Design Solutions in Landscape Architecture and Contemporary Trends in Landscape Architecture (Van Nostrand Reinhold, John Wiley & Sons, 1997). His book Green Roofs in Sustainable Landscape Design (WW Norton, 2008), provides definitions of the types of green roofs and sustainable design, studies European models, and focuses on detailed case studies of diverse green roof projects throughout North America. In 2010 the green roofs book was one of thirty-five nominees for the 11th annual literature award by the international membership of The Council on Botanical & Horticultural Libraries for its “outstanding contribution to the literature of horticulture or botany.”

Steven’s most recent book is Professional and Practical Considerations for Landscape Design (Oxford University Press, 2020) where he explains the field of landscape architecture, outlining with authority how to turn drawings of designs into creative, purposeful, and striking landscapes and landforms in today’s world.

He has been a regular attendee and contributor at various ASLA, green roofs and other conferences in landscape architecture topics. In recent years Steven has had more time for music activities, as a solo pianist and accompanist.

Steven joined the Greenroofs.com editorial team in December, 2013 as the Landscape Editor. In February, 2015 he completed his 14-part series “A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective.”

Signe Nielsen, FASLA

Principal, MNLA (Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects, P.C.)

Photo by Brian Pierce

Signe Nielsen has been practicing as a landscape architect and urban designer in New York since 1978. Her body of work has renewed the environmental integrity and transformed the quality of spaces for those who live, work and play in the urban realm. Ms. Nielsen believes in using design as a vehicle for advocacy to promote discourse on social equity and community resilience and has served on multiple panels to effect positive change. A Fellow of the ASLA, she is the recipient of over 100 national and local design awards for public open space projects and is published extensively in national and international publications. Ms Nielsen is a Professor of Urban Design and Landscape Architecture at Pratt Institute in both the Graduate and Undergraduate Schools of Architecture and currently serves as President for the Public Design Commission of the City of New York. Born in Paris, Ms. Nielsen holds degrees in Urban Planning from Smith College; in Landscape Architecture from City College of New York; and in Construction Management from Pratt Institute.

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture

My Site

Such great website

Amazing blog thanks for sharing today on this blog