A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island, Part 3 of 3

Images by MNLA are noted; all others are by ©Steven L. Cantor

From Part 1 – NARRATIVE AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION:

Concept: Principal of MNLA (Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects), Signe Nielsen describes her concept for Little Island, the fanciful 2.4-acre park appearing to float like a magical green carpet above the eastern edge of the Hudson River by Pier 54 and 56, “as a leaf with upturned edges.”[1]

Part 1: Narrative & General Description; Little Island South Bridge entrance. Image: MNLA

See A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island – Part 1 by MNLA…

Part 2: Plantings, Structural Systems & Engineering.

See A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island – Part 2 by MNLA…

Final: Little Island MNLA Part 3 of 3

Most of this section is based on a Zoom interview with Signe Nielsen on December 6, 2021. Unless otherwise noted, quotations from her are from that interview.

Walking along the edge of the lawn.

PAVEMENTS AND CONSTRUCTION DETAILS

Hanover Pavers and Volkanite™: There were many pavement designs at various times, such as terrazzo, and various other materials. Throughout the site the color palette was in warm tones with bronze railings, wood, and weathering steel.

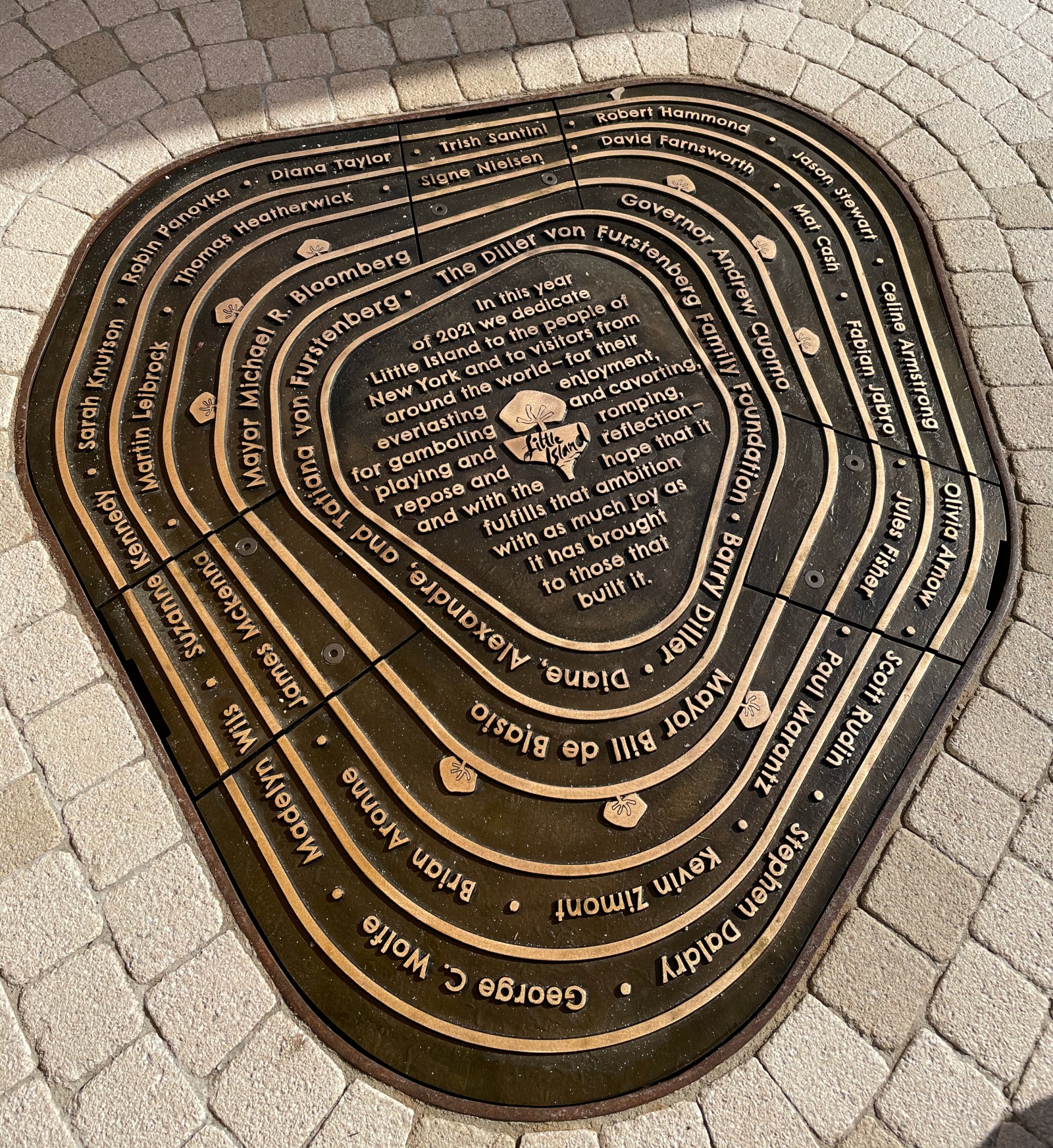

“Once we convened and agreed on this color palette Barry Diller did not want to have the tulip pot geometry to telescope up into the paving. Barry had gone through a period where he wanted more whimsy and thought of the idea of dropping a pebble into a pond, and that became the concept for the manhole in the center of the plaza. It’s maybe 3 feet by 2 feet, with a dedicatory inscription on it. Ripples of color emanate and create the ripples; the center is the lightest color, the outermost is darkest. Originally there were seven colors, and the darkest color eventually was dropped (Barry didn’t want it).”

Pavers view from the northeast. Image: MNLA

The plaza.

Volkanite™ “fish.”

Narrowing of plaza towards the south bridge.

Each band includes a smattering of colors from bands of colors from either side of it. Because the curves were so complicated, we settled on 4 x 4 rather than 4 x 8 or 8 x 8 pavers. MNLA mocked-up tumbled and non-tumbled finishes; they settled on a tumbled finish, with porous joints.

Paver detail. Image: MNLA

Pavers were installed on an asphalt base. Image: MNLA

Volkanite™ paver layout. Image: MNLA

Pavers pre-joint filler. Image: MNLA

Pavers at the end of construction. Image: MNLA

Pavers in winter. Image: MNLA

The pavers sit on top of a bituminous setting bed on top of a concrete slab. Volkanite™ pavers, manufactured in Great Britain, serve as the imaginary schools of fish in the body of water, darting through the ripples.

Boulder Scramble: The quartzite stone weighs 175 lbs./CF, and the largest boulder is about 5’ x 3’ x 3’ and weighs about 8,000 lbs. The boulder scrambles integrate seamlessly with ADA compliant walks. However, the scrambles were closed for redesign and reconstruction in part because they were very popular with everyone. Somewhat unexpectedly, many people were sitting on them. People of all ages and abilities were using them.

Boulders for scramble on delivery. Image: MNLA

Starting point of the boulder scramble.

Arrival to the walk from the boulder scramble.

Image: MNLA

One full section of the boulder scramble between walks.

“Sometimes, those abilities were not sufficiently agile, and people would look down and see a huge step and walk around into the landscape, and there was an ever-expanding zone of trampling around the boulder scrambles. So, what we’ve decided to do is add intermediate steps. So, on some of the high risers between boulders, we’ll add intermediate boulders, so that it is more suitable for older, less agile people or children or people in tighter skirts [so that they can manage to navigate without resorting to walking through the landscape.]”

The problem occurred only on the southwest side, not on the east side—hard to tell why. Signe explained that they really didn’t want to put in plant rails, handrails, or guardrails, as the only problem was people sitting on the stones.

A last resort strategy was to make them non-contiguous where they don’t actually connect past the path, but actually just occur as sitting opportunities floating in the lawn or landscape.

Intersection of the boulder scramble walk.

The boulder scramble is set within plantings and the sheet pile.

The boulder scramble is attractive to many people, children included.

Boulder scramble with people sitting. Image: MNLA

The boulder scramble up close.

Under Signe’s direction, MNLA’s construction crew did add additional boulders, tightened the arrangements, and corrected the issue. They will will be replanting in early spring.

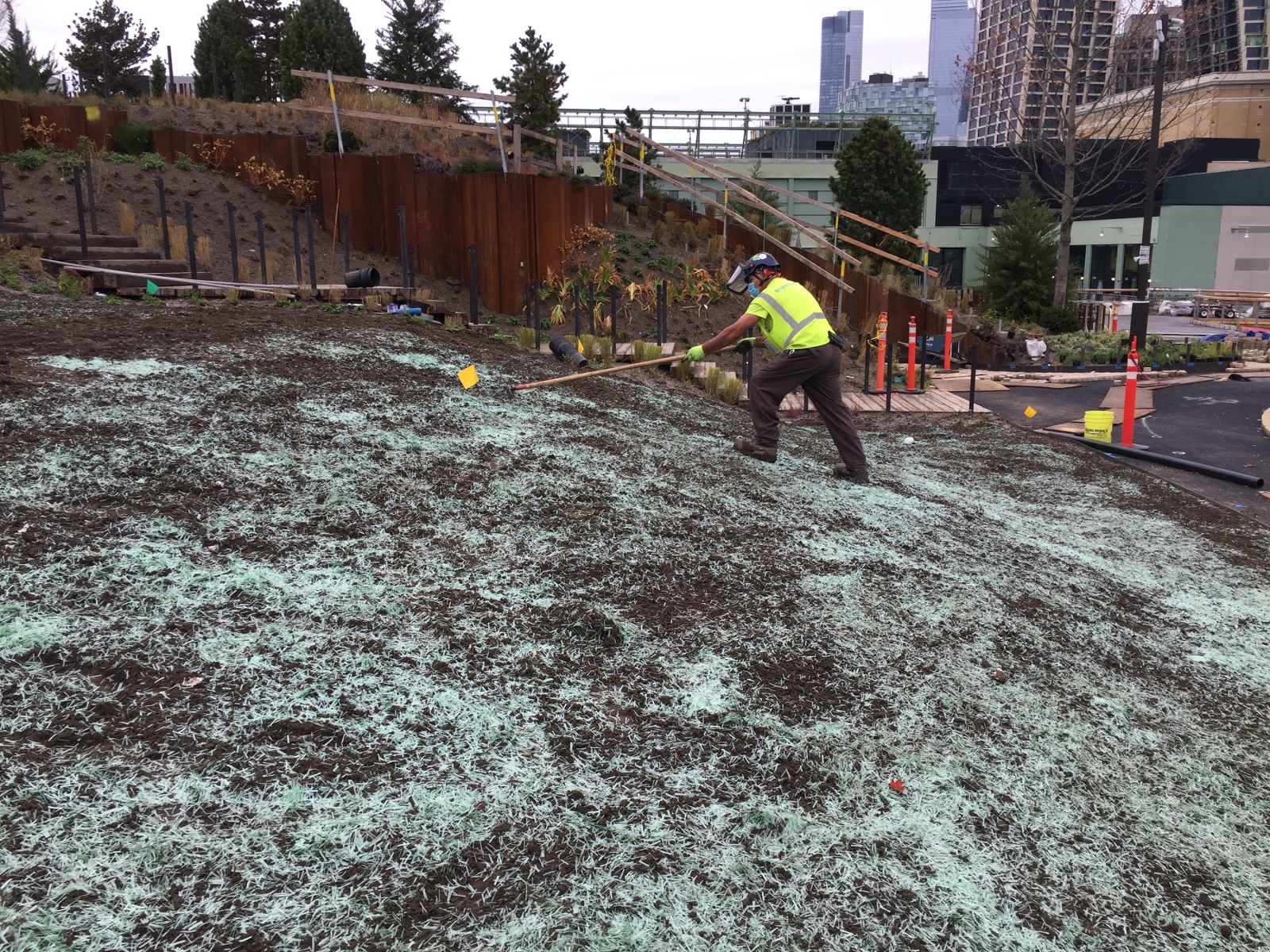

Geofiber: Strips of plastic, two inches long, like shredded cassette material, standard product, comes in three colors, black, clear, and brown.

“We used clear. The brown was too brown, the black was too weird, and I just went with clear. It’s really invisible. It’s mixed integrally with the soil.”

Tilling the geofibers on the lawn. Image: MNLA

Geofibers on a steep slope. Image: MNLA

Soils are all manufactured. MNLA didn’t have much staging area on the pier, so most material was craned or telebelted. Sometimes it was craned in large white bags, but most of the soil was telebelted into place. The telebelt could take geofiber soil.

“Many landscape architects hire soil scientists to design their soil, we did not. I’d never used geofibers. I called up a geofiber expert. How do I know how much geofiber to specify and what length? It was available in three sizes: 1-1/2”, 2” or 2-1/2”. He said send me your steepest slope and the length of that slope and I’ll tell you. The formula of erodibility was a factor. A long slope length creates an exponential erodibility factor. We did not have very long slopes, and he was pleased, so ours wasn’t that challenging. We used geofiber on Little Island for slopes steeper than 1:2.5.”

Five Different Soil Types: There are four types of soil mix: but essentially they consist of three types of soil, two which have a variation on a theme. Type A and B are both sand-based loam; one has a higher proportion of organic matter than the other, which is the only difference between the two.

Soil Type A with and without geofiber. Image: MNLA

Soil Type A with tarp protection. Image: MNLA

Soil Type B brought in via telebelt operation. Image: MNLA

“The variations, which we could call C and D on those two types, are due to geofibers. We called for geofibers on slopes greater than 40% and all the way to 100% or 1:1. The fifth type of soil is structural soil. “The structural soil is only used where we need a root path for a large tree which is hemmed in on three sides, such as the Kentucky Coffee Tree at an S curve, with a path on three sides, so that roots have access to larger soil volumes all around. That’s the ONLY reason structural soil is used.”

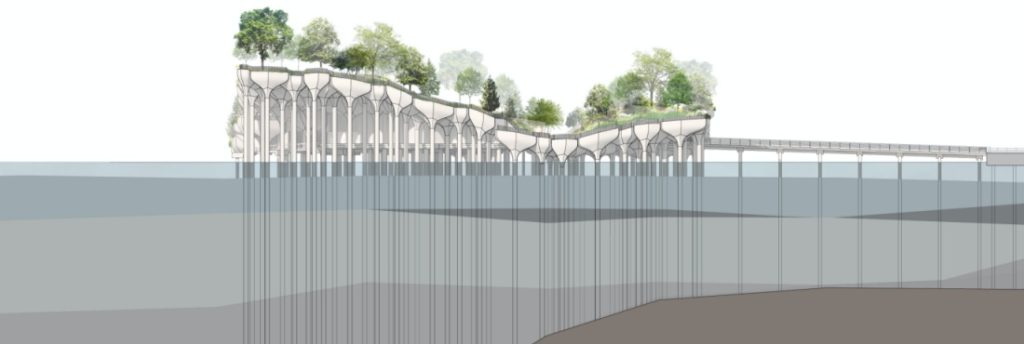

Sheet Piles:

Boulder scramble nestled against sheet piles with planting pockets.

Sheet pile with drooping Delosperma (ice plant). Image: MNLA

Sheet pile with Aster, Pinus mugo ‘Jakobsen’ (Jakobsen mugo pine). Image: MNLA

Sheet piles with steps near the arrival from the south bridge.

“We did a slope analysis, anywhere slopes were steeper than 1:1 and where we needed to retain soils and get volume for a tree or an opening for a bathroom or the undercroft entrance. Those became locations for sheet piles, which are as tall as 12 feet. They’re used to create the dramatic slope up to the high point of the southwest lookout platform at elevation 62; they are essentially retaining walls.

Their purpose varies, sometimes it’s to tuck the bathrooms into the landscape, sometimes literally it’s retaining soil volume for trees, retaining paths, intermediately placed to lessen severity of slopes — all the ways a landscape architect would think about a retaining wall.”

The amphitheater is nestled between the southwest and northwest landforms to spectacular effect.

If you compare the cost, sheet pile was a significant savings of time, material, and was also readily available. It was a major savings over the cost of gabions as well, and a major savings in soil volumes.

“Barry (Diller) was reluctant at first to use industrial, rather mundane materials, but gabions and solid rock, and other choices were too heavy, and incredibly expensive.”

Sheet pile walls cost about $95/ sf or $1.9 million for 19,920 sf of walls. If gabions had been used instead, they were estimated at $15 million although it’s hard to make an exact comparison.

The sheet pile retaining walls with planting pockets form backdrops for the steps.

Plantings at the base and at the top of sheet piles.

Sheet pile with Parthenocissus (Virginia creeper) and Campsis radicans (trumpet vine). Image: MNLA

“Why not use a material specified in basic marine construction for bulkhead material that takes up no space? It’s 3/8” thick and takes up no space horizontally in the landscape and by virtue of the fact that they are crenelated at the top and the bottom, they are perfect for pockets for planting perennials that flop over at the top and nooks for vines at the bottom. The choice of sheet piles was one of the most inspired selections of materials that we made on the project!!”

Steel Straps: Steel straps for planting trees were used for every tree, not just hero trees. Anchored to the deck (slab) forever, a stainless steel cable is used, that has an epoxy grouted anchor into the concrete slab. Those cables are carried through the geofoam and soil and are necessarily extra long.

Sheet piles bracing pre-footing. Image: MNLA

Steel guy wires and straps. Image: MNLA

Steel anchors and straps for oaks. Image: MNLA

Once the rootball was placed, straightened, oriented properly, and set at the right elevation, and before the burlap was cut off the rootball, the arborists put wide straps of reinforced non-degradable mesh in the shape of a square which formed a frame to which the cables were attached and tightened in place. There were four to 10 cables per tree, subterranean belt and suspenders. On slopes, more cables were set on the uphill side. More were placed on the windward side, fewer on the leeward side.

Lightning Rods: A couple of lightning rods on the pier occur at the very highest point on a pole with mounted security camera, WIFI and lightning rod. There are three or four lighting rods, one on each corner.

Lightning rod with redtail hawk. Image: MNLA

The SW overlook (the highest elevation in the park) is closed in times of very high winds and lighting. It’s an open question whether lightning rods might be placed on hero trees in the future?

Irrigation: With the exception of the turf, all landscaped areas are irrigated using a drip system.

Drip irrigation valve manifold. Image: MNLA

Lawn irrigation spray heads. Image: MNLA

The small to medium size trees (up to 8” caliper) use multiple loops of drip tubing on top of their root balls. The hero trees have additional irrigation using deep drip watering stakes to penetrate the clay root balls. The lawn is irrigated with a standard pop-up system.

Lighting: Lighting dramatizes, highlights, and washes the features of Little Island while ensuring safety.

Specimen trees washed with uplights.

Lighting combines clarity and mystery.

Lighting stairs & uplights. Image: MNLA

There are three basic strategies: the ambient lighting is done by uplighting the trees which creates a dramatic effect both within the park and from a distance. The paths and stairs are illuminated from under railing lights that provide a continuous wash of light where people walk and help accentuate the paths of travel. Because the majority of paths are of a gradient that requires handrails, there is ample opportunity to use this lighting technique.

In order to avoid cluttering the large paved plaza, pole lights with multiple fixtures are dotted within the landscape and are aimed toward the center to cast an even glow of light.

The Little Island lawn is a popular place for watching the cityscape at night.

Lighting pot break. Image: MNLA

The infrastructure is highlighted.

Tulip pots lit.

Then there is accent lighting wherein the pot forms are uplit from below. No light is cast on to the water which could harm marine life. All the lights can be dimmed so, for example, on performance nights, the lights can be dimmed and elevated afterwards to assist with egress.

Little Island lighting overview. Image: © Elizabeth Felicella courtesy of MNLA

The amphitheater has its own state-of-the art lighting and audio-visual system for the stage and seating areas.

Interactive Musical Chimes and Temporary Sculpture: Two music activated chime-like play devices have been placed near the entrances, one in the elbow of the North Bridge, the other in the Southeast Overlook, where both attract a lot of interactive attention from passersby.

Organ on the north bridge. Image: MNLA

Dance Chimes. Image: MNLA

The concern has been that despite their obvious attraction to passersby, they could create congestion issues during busy periods and distract from other major features of Little Island.

Sculpture.

Clever impact but concentrates people.

Is it appropriate?

Similarly, along the walks climbing two of the hills are a pair of rotating disks, each bolted to the guardrails, with a hypnotic effect on pedestrians, almost as if one is suddenly at the entrance to a carnival or circus sideshow. They are a clever design, but are they a necessary installation along a narrow walk amidst a beautiful landscape? Without them, the park provides a balanced array of well spaced-out features without added intrusions.

Consultants

Little Island consultants’ manhole cover located in the plaza center. Image: MNLA

- Architect: Heatherwick Studio

- Structural/MEP Engineer: Arup (MNLA consultant)

- Marine Engineer: Mueser Rutledge (MNLA consultant)

- Lighting: Fisher Marantz Stone

- Architect of Record for amphitheater and restrooms: Standard Architects

- Landscape Architect: MNLA (they were also the “Architect of Record” for everything but the amphitheater and restrooms)

- Irrigation: ICI (MNLA consultant)

- Signage: C & G Partners

Agencies

- Hudson River Park Trust (HRPT, owner of the land/water)- Pier 55/Little Island is state-owned land

- NYS Office of General Services

- NYS Department of Environmental Conservation

- US Army Corps of Engineers

- NYC Department of Environmental Protection (water supply)

- NYC Department of Transportation (new crosswalk at 13th Street and layby along the highway)

- NYC Fire Department

Donor

- Diller-Von Furstenberg Foundation

- Operating Not-for-Profit for duration of lease between HRPT and Little Island

CONCLUSION

Lighting overview of Little Island. Image: MNLA

Although essentially finished, Little Island remains a work in progress. A creation of many micro-climatic ecologies, some of which are evolving as the plantings become established, Signe Nielsen acknowledges that some plantings will need to be enhanced or occasionally replaced as conditions change.

As hero trees create shade, some perennials that were in full sun will need to be replaced. As some areas that are wet may dry out, or vice versa, some adjustments may need to be made; yet for the most part, a remarkably complex landscape is evolving as intended, and has already withstood severe weather while attracting diverse groups of visitors who are glad to participate in all the activities offered. Will every hero tree become truly heroic? Let us hope so.

Image: MNLA

Cumulative 3-part “A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island by MNLA, Heatherwick Studio, Arup & others” Series End-notes

Read Part 1 of A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island by MNLA, Heatherwick Studio, Arup & Others to see end-notes 2-11.

Read Part 2 of A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island by MNLA, Heatherwick Studio, Arup & Others to see end-notes 12-14.

Publisher’s Note:

See the Little Island Project Profile in the Greenroofs.com Projects Database.

Steven L. Cantor, Landscape Architect

Photo by Thomas Riis

Steven L. Cantor is a registered Landscape Architect in New York and Georgia with a Master’s degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He first became interested in landscape architecture while earning a BA at Columbia College (NYC) as a music major. He was a professor at the School of Environmental Design, University of Georgia, Athens, teaching a range of courses in design and construction in both the undergraduate and graduate programs. During a period when he earned a Master’s Degree in Piano in accompanying, he was also a visiting professor at the College of Environmental Design at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He has also taught periodically at the New York Botanical Garden (Bronx) and was a visiting professor at Anhalt University, Bernberg, Germany.

He has worked for over four decades in private practice with firms in Atlanta, GA and New York City, NY, on a diverse range of private development and public works projects throughout the eastern United States: parks, streetscapes, historic preservation applications, residential estates, public housing, industrial parks, environmental impact assessment, parkways, cemeteries, roof gardens, institutions, playgrounds, and many others.

Steven has written widely about landscape architecture practice, including two books that survey projects: Innovative Design Solutions in Landscape Architecture and Contemporary Trends in Landscape Architecture (Van Nostrand Reinhold, John Wiley & Sons, 1997). His book Green Roofs in Sustainable Landscape Design (WW Norton, 2008), provides definitions of the types of green roofs and sustainable design, studies European models, and focuses on detailed case studies of diverse green roof projects throughout North America. In 2010 the green roofs book was one of thirty-five nominees for the 11th annual literature award by the international membership of The Council on Botanical & Horticultural Libraries for its “outstanding contribution to the literature of horticulture or botany.”

Steven’s most recent book is Professional and Practical Considerations for Landscape Design (Oxford University Press, 2020) where he explains the field of landscape architecture, outlining with authority how to turn drawings of designs into creative, purposeful, and striking landscapes and landforms in today’s world.

He has been a regular attendee and contributor at various ASLA, green roofs and other conferences in landscape architecture topics. In recent years Steven has had more time for music activities, as a solo pianist and accompanist.

Steven joined the Greenroofs.com editorial team in December, 2013 as the Landscape Editor. In February, 2015 he completed his 14-part series “A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective“and a survey of green roofs in Copenhagen Green Tour 2015.

Signe Nielsen, FASLA

Principal, MNLA (Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects, P.C.)

Photo by Brian Pierce

Signe Nielsen has been practicing as a landscape architect and urban designer in New York since 1978. Her body of work has renewed the environmental integrity and transformed the quality of spaces for those who live, work and play in the urban realm. Ms. Nielsen believes in using design as a vehicle for advocacy to promote discourse on social equity and community resilience and has served on multiple panels to effect positive change. A Fellow of the ASLA, she is the recipient of over 100 national and local design awards for public open space projects and is published extensively in national and international publications. Ms Nielsen is a Professor of Urban Design and Landscape Architecture at Pratt Institute in both the Graduate and Undergraduate Schools of Architecture and currently serves as President for the Public Design Commission of the City of New York. Born in Paris, Ms. Nielsen holds degrees in Urban Planning from Smith College; in Landscape Architecture from City College of New York; and in Construction Management from Pratt Institute.

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture