Staff of Environment America writes:

Pollinators – bees, butterflies, moths, wasps, flies, beetles, ants, bats, hummingbirds and others – are a vital component of the planet’s ecosystems. Almost 90% of all flowering plants and more than a third of the world’s crop species depend on them. Countless species of birds and mammals feed on fruits and seeds that couldn’t exist without them. With pollinator populations in steep decline, it is becoming ever more crucial to ensure that these imperiled creatures have safe havens in which to thrive.

Environment America Authors: Steve Blackedge, Marcia Elridge and James Horrox

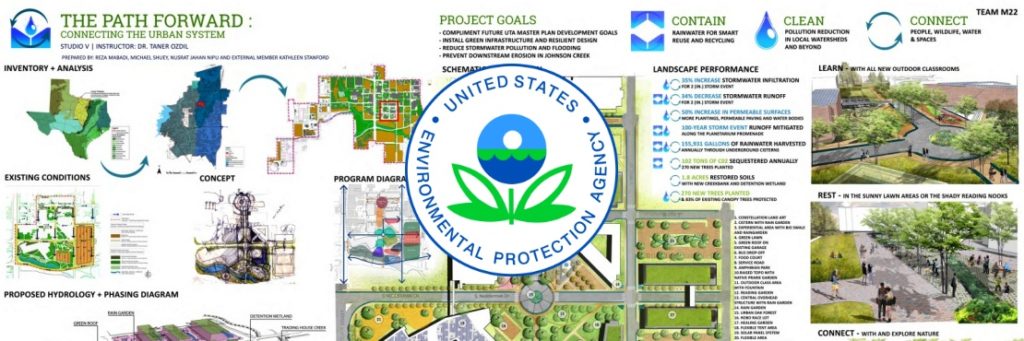

Through the smart use of so-called “green infrastructure,” the same urbanized landscapes that are eating up wildlife habitats with such devastating effects also present opportunities to create those havens.

Green infrastructure can take many forms, from the humble street tree to green stormwater infrastructure like the bioswales and rain gardens now used in many cities to manage stormwater runoff and mitigate flooding. Much of this infrastructure can double as a thriving wildlife habitat, and some can be particularly beneficial to pollinators.

While each species has its own specific habitat needs, there are two that are common to all pollinators: an abundance of diverse, flowering native or naturalized plants, and safe places to nest and breed.

Living roofs (aka Green Roofs)

Among the most effective (and cost-effective) forms of nature-based urban infrastructure in meeting these needs are “living roofs” or “rooftop meadows” planted with wildflowers and native grasses and/or other native or naturalized pollinator-friendly plant species.

High above the city streets, even in the densest urban settings, these hotbeds of biodiversity can support all kinds of pollinators, from bees and butterflies to birds, bats, flies and ants. They can be particularly valuable to bees, especially when they are planted with diverse native forbs (flowering, non-grassy herbaceous plants) to provide foraging resources and designed to take into account the differing nesting habits of different bee species. (Interestingly – and perhaps counterintuitively – research has suggested that living roofs can also enhance the performance of rooftop solar panels.)

Where living roofs have been planted to restore lost pollinator habitat, the results have often been quite extraordinary. The six-acre roof meadow of the Vancouver Convention Center, for example – “the only and largest coastal meadow” in downtown Vancouver – is planted with more than 400,000 indigenous plants and grasses, providing habitat for birds, insects and other creatures. Since it was built in 2009, 250 types of insects have been seen on the roof, including two species of pollinator previously thought to be extinct in the Vancouver metro area.

Natural elements can be incorporated into the design of our buildings in numerous other ways. “Living walls,” for example, can host a wide range of different plants, from grasses, shrubs, ferns, succulents and herbaceous plants to all manner of vegetables and herbs, and when designed with the needs of specific species in mind, can potentially be a promising pollinator habitat.

Local agencies can lead by example, from installing green roofs and walls on municipal buildings to transforming roadsides into pollinator habitat and implementing other citywide initiatives to weave pollinator-friendly living elements into the urban fabric across other publicly managed green spaces.

Read more: How to make our cities a home for bees, butterflies and other pollinators

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture