High Line Redux, Part 2

All Photos by and ©Steven L. Cantor, ASLA Except as Noted

From High Line Redux, Part 1: I previously presented a series of photographic essays on the High Line in 2013-2015, A Comparison of the 3 Phases of the High Line 14-Part Series.

It’s stimulating to revisit this now much more well-established park, although a work in progress because major construction is still occurring adjacent to it. Even though the High Line was at first completely closed during the COVID-19 lockdown, park management has found effective ways of opening it during the pandemic, and the public has clearly relished it as an open space system and garden, and a place for exercise, fresh air, conversation, and art.

Rather than a long essay, I offer bulleted points and thoughts for your consideration in two parts from additional High Line walks of November 2022 and December 2021:

Final High Line Redux, Part 2

Publisher’s Note: See High Line Redux, Part 1

16. Simpler treatments work better. The more complex design occurs when the High Line traverses Chelsea at an angle, creating the need for more irregular geometries of planting beds and pavements, which in turn, result in eccentric juxtapositions and sometimes peculiar alignments between plantings and pavements.

Simplest is best.

17. Throughout there is effective night lighting, but sometimes too many overlapping techniques. Perhaps, the most pleasingly dramatic is the strip of lighting under the shiny guardrails running the length of the route on either side. At night the effect can be magical.

Guillermo Galindo’s “Fuente de Lagrimas (Fountain of Tears)” is made from the water stations that volunteers leave near the US-Mexico border to serve those attempting the crossing. The sculpture, which commemorated migrants in the desert, was beautifully night-lit, but was removed last year and the sculpture that takes its place is of a spinning gyroscope form within the view of diverse architecture and plantings of the High Line corridor.

Strip lighting on either side of the High Line illuminates quite effectively the entire pedestrian route and also highlights the sculptures. Other techniques of lighting, such as short posts and strips are used as well.

18. The art program is well organized, on a rotating calendar that provides different installations every six months, sometimes longer. The artists range from well established to emerging talents. Competitions are held in which the public is permitted to vote their preferences for selecting two finalists for sculptures for the Plinth, among twelve scale models put on display on the High Line.

A view of the Plinth from street level.

One of the scale models of proposed sculptures.

Three views of “Brick House” by Simone Leigh (June 5, 2019 – May 2021), which commands the Plinth from any direction – a remarkable and powerful composition.

“Untitled,” a sculpture of a large airborne drone hovering over the Plinth by sculptor Sam Durant, gains more importance with the use of drones in modern warfare in Ukraine.

Hannah Levy’s “Retainer,” a larger-than-life set of braces, rests uncomfortably on a small plaza on the High Line.

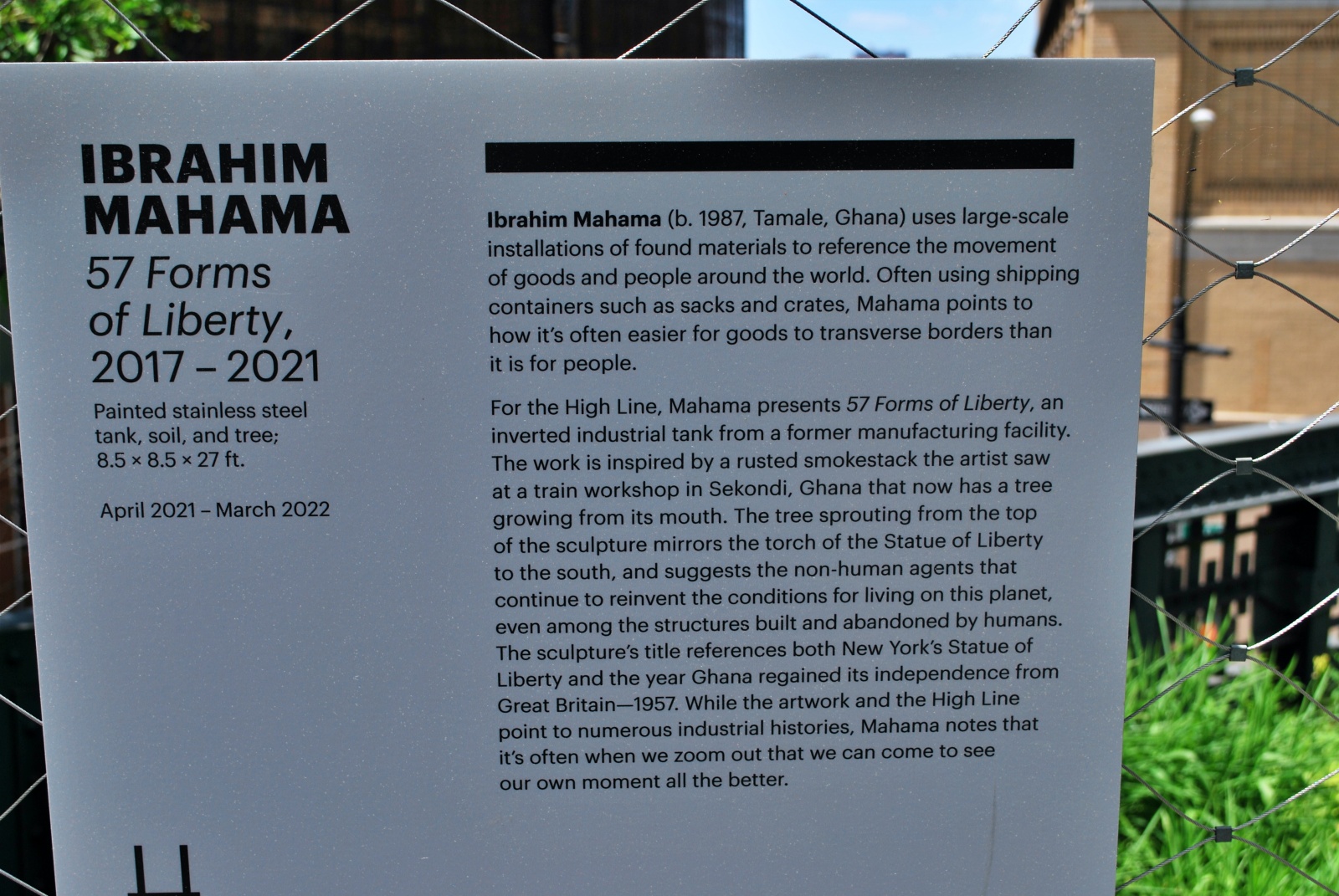

19. The art installations are often remarkable but less consistently successful. (This is my subjective judgment: Some seem to bear no relationship to the setting in which they are placed or are poorly constructed or even innocuous). When placed within the plantings they sometimes become so absorbed by the plant growth as to become unnoticeable, so they must be loud and bold. In the few locations such as the Plinth where the design has been conceived from the beginning as a space for the display for sculpture, the results are consistently far more powerful. Clear graphics identify the artists and their sculptural works.

Nina Beier’s graceful and evocative group of figures “Women and Children,” set within the High Line landscape, often draws a crowd of spectators as the figures weep rivulets of water into a hidden pool. It’s quite dramatic.

Pedestrians compare notes and images of Naama Teabar’s “Equal Measure,” a giant metronome. In the past some sculptures, such as the immensely popular bird cage/feeders by Sarah Sze, actually flanked both sides of the major walks – as seen below – and created traffic jams as pedestrians interacted with the bird feeders.

Sarah Sze’s “Still Life with Landscape – Model for a Habitat” on 6.10.11. The pedestrian corridor became a bit crowded.

“Urban Rattle” by Charlie Hewitt.

“The Baayfalls” by Jordan Casteel. The dynamic mural adds a striking tapestry on a wall adjacent to the High Line at 22nd Street.

At the same time as crowds are flocking back to the High Line, should this behavior be encouraged when the pandemic is still lurking and new variants could potentially spread more easily in tightly clustered groups of people? Why encourage potentially risky behavior? The High Line, Little Island, nor any major outdoor activity space need not develop a reputation as a super-spreader haven instead of a place to enjoy outdoor activities, interactions with friends, and remarkable landscapes.

20. When placed on the pavements where people are walking and congregating, at times the sculptures interfere with the flow of traffic, all the more so when the High Line is crowded with people. The pandemic brought about a great lessening of intensity of use so this was not as much of a problem in recent times, but as activities return to a more normal pattern, the difficulties may reoccur. Recently, many of the sculptures which have been in place for months have been removed, no doubt to make way for the next round of installations. It’s an interesting exercise in appreciation of the High Line’s green roof design and its spectacular setting to walk past these spaces and notice how successful they appear sans art.

Juxtaposing the area without sculpture above and without, below. Hannah Levy’s “Retainer” below doesn’t inspire trips to the orthodontist but does add a touch of humor – yet how many times does one need to see it?

21. Yet, art is a consistent theme of the High Line; it’s an interdisciplinary work.

I tend to object to removal of mature plants in order to insert a sculpture. I’d prefer to see a planting bed with 6 or 8 species of perennials co-existing as a background or foreground for a work of art. Think alone of the time involved in removing mature plantings and preparing an appropriate space in which to place that sculpture.

Why not save those funds and give them to an artist or sponsor a gallery near the High Line to display an artist’s work? Some of the sculptures are site specific to the High Line but many would be suitable or even more effective in another setting. Or if the trend continues to be to zone for taller buildings which will permit less light to reach the narrow strip of the High Line, why not give over a few entire blocks to artists and sculptors and see what they can manage to create to humanize and animate what remains of public space while foregoing forlorn plantings altogether? At the same time the proliferation of new architecture along the entire corridor of the High Line has created spectacular sculpture on a gigantic scale that tends to minimize the impact of installations in individual locations unless they are unique, such as those on the Plinth or the 26th Street Viewing Spur. Why add another boulder, even a beautiful one, to the Grand Canyon?

22. The artists are undoubtedly highly skilled and accomplished. They deserve employment. Some of the sculptures and murals enliven and animate the spaces, provide symbolic or real commentary on contemporary life and social issues, generate interest and income, for the artists as well as the galleries within the neighborhoods and nearby communities. Some visitors may come primarily to see the art. In earlier years remarkable billboard art trumpeted displays just over the parapet walls of the High Line, but as buildings were erected on either side, there has been a notable decline in such bold graphics.[6]

Raúl de Nieves, part of his 3-figures for “The Musical Brain” (April 2021-March 2022), a group exhibition that reflects on the power music has to bring us together.

The change of seasons beautifully offsets this sculpture by Ibrahim Mahama, “57 Forms of Liberty,” from April 2021 – March 2022.

Above and below from November, 2014 in my A Comparison of the 3 Phases of the High Line 14-Part Series Part 4: Signage and Graphics.

23. Some interdisciplinary events are inspired, such as the Mile Long Opera, composed by David Lang with text by poets Anne Carlson and Claudia Rankine, an immersive musical experience involving about 1,000 singers, each illuminated, in costume and stationed at key locations along the full course of the route. This was a marvelous creation for a limited number of audience members: Singers or other performers were stationed at key points where they would have the most impact during about a week’s run in the evenings in October, 2018.[7]

Image: Cedric Tolley

On the High Line at dusk near 14th Street the artist Cécile B. Evan produced A Screen Test for an Adaptation of Giselle through late January 2022, “an evolving adaptation of the industrial-era ballet.” It seemed quite fascinating, although I was unable to attend a performance.[8]

Photo by Cécile B. Evans, A Screen Test for an Adaptation of Giselle, 2019 (still). Courtesy of the artist; via The High Line.

24. Patrick Moynihan Train Hall, (named after Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the United States Senator who proposed its use), built into the grand edifice of the former McKim Meade and White Post Office Station, is now within eyeshot of the termination of one arm of a newer, yet graceful tentacle of the High Line, the Spur. It climbs gracefully, but ends abruptly at West 30th Street and Tenth Avenue with an elevated plaza and a platform called the Plinth for display of sculpture and affords pedestrians views in all directions so that they can appreciate the sculpture as well as anticipate their next destination, almost as if they’re leaving a ship and heading towards shore. Giant sculptures seem quite appropriate here, and there is no competition from the plantings; in fact, evergreens help form a backdrop. A $50 million extension was proposed to connect to the Moynihan Train Hall.[9]

Construction is well under way of this link from the Plinth; the High Line – Moynihan Train Hall Connector is expected to be completed by the spring of 2023.[10] Upon its completion, it will clearly add convenience for people using the terminal and wishing to access the adjacent neighborhoods as pedestrians, although it’s worth wondering how much additional traffic will occur, and whether its popularity could contribute to overcrowding.

It’s exciting to see its skeleton in place and to anticipate its completion.

Four views of the Moynihan Train Station.

25. At a distance as one walks north, the towering spires of Hudson Yards appear like the sci-fi “Transformers”: Their tenuous slenderness and angles lend them a disarming and surprising delicacy.

The contorted tops of some Hudson Yard towers give a sense of science fiction in reality.

At the street and pedestrian level, the design is coarser. The plantings are designed for horticultural display, with annuals such as salvias and petunias. The pavement designs are chaotic. One of the main features is a wide vehicular drop-off lane that interferes with pedestrian functions.

The vehicular drop-off lane intrudes into the pedestrian spaces.

Adjacent hotels and businesses borrowed some of the High Line’s vocabulary, but it lacks cohesion. Many of the pavement patterns knock into one another weirdly.

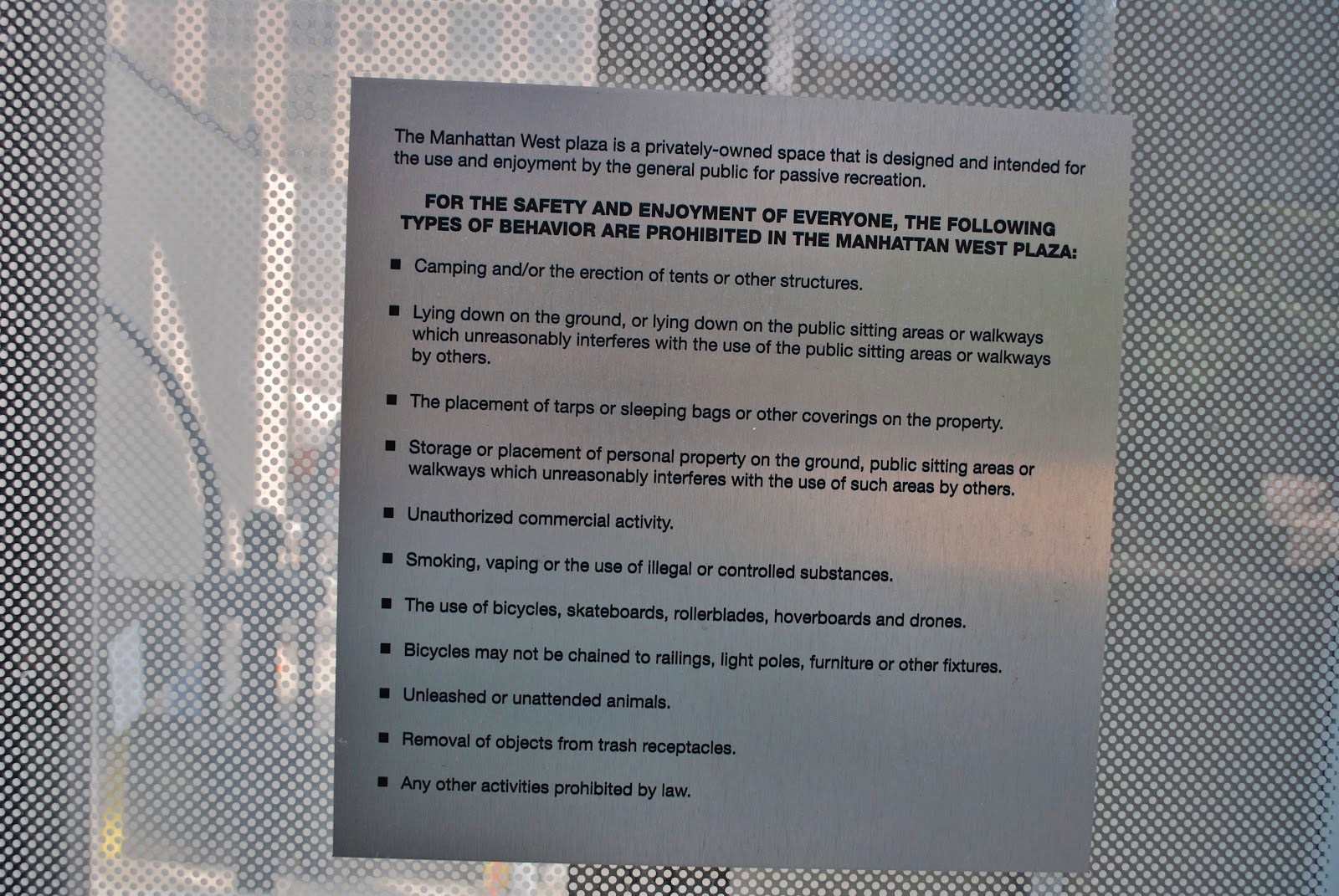

Manhattan West Plaza, an adjacent development, borrows some of the same vocabulary as the High Line, but is stiffer and has planting beds which lack the integration of its neighboring inspiration. Its rules and prohibitions also seem more proscriptive.

26. The “Interim Walkway” of the High Line from the Jacob Javits convention center and wrapping around Hudson Yards is still evolving as the train yards are being developed. Often this loop is closed and under construction. Although signs posted in May, 2021 stated that it would be re-opening soon that had still not occurred as of mid-October 2022. As of spring, 2023, I believe it’s open intermittently. Another proposal for about $60 million would link the Javits Center to the Hudson River Park.

The Interim Walkway in late 2014.

27.

Phase I and II cost: $153 million

Phase III: $76 million

Moynihan Station: $50 million (announced by New York Governor Kathy Hochul)

Hudson River Park: $60 million (proposed)

Total Budget: $339 million

28. Many businesses in Hudson Yards closed during the COVID-19 crisis and have not re-opened, with some having to fold. Related Companies, the developer of Hudson Yards, received many tax incentives and other benefits from New York City. That many businesses have gone bankrupt and others are empty has raised alarms. As the pandemic has slowed down, the completion of some phases of work has resumed.

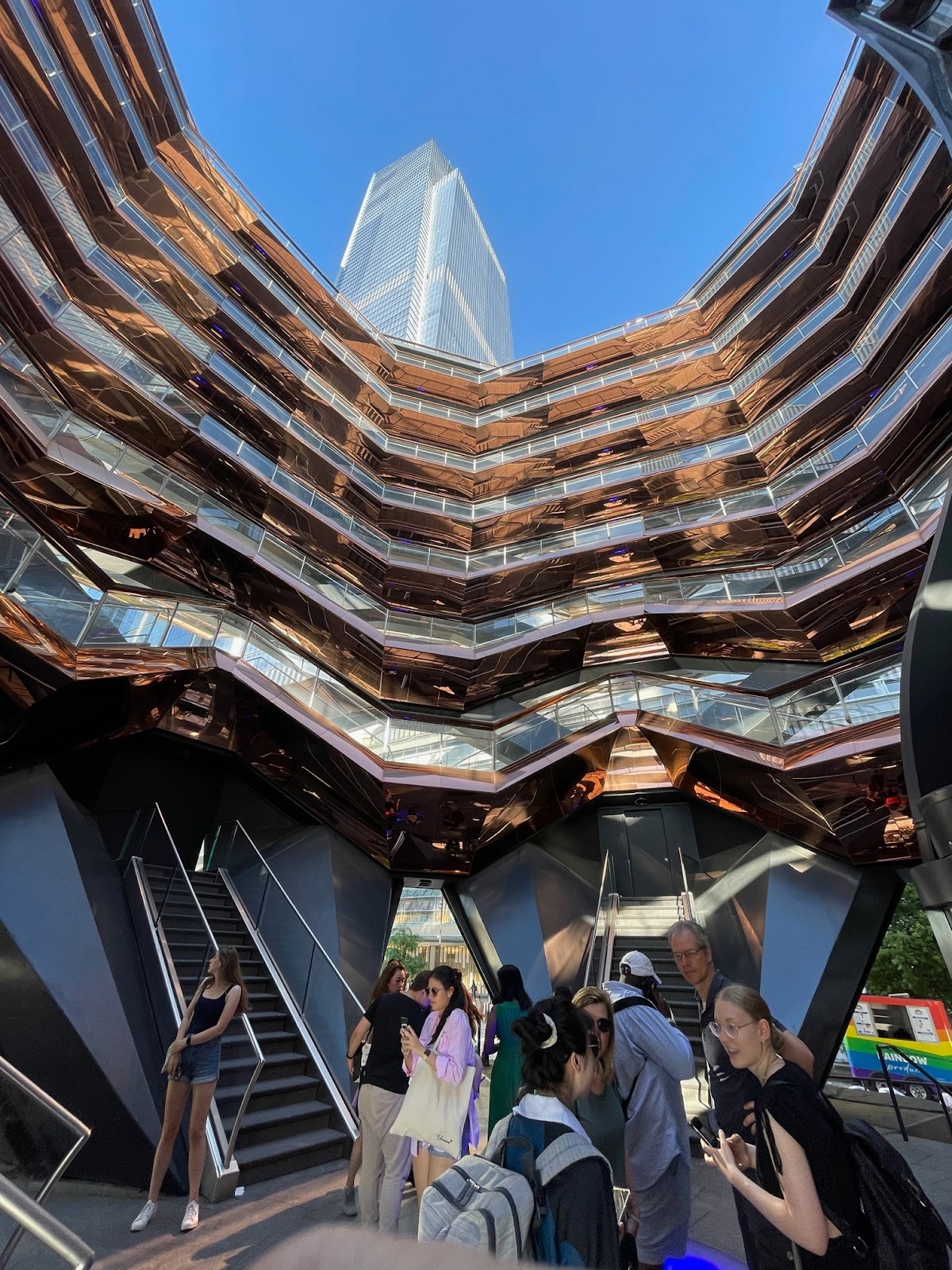

A towering sculpture of spiraling staircases 150 feet tall called the “Vessel,” designed by Heatherwick Studio, looming prominently in the center of Hudson Yards on which people could climb to the top and have excellent views, was closed to the public after several people used it as jumping off point for suicides. It has the appearance of a strong, shining sculpture, a hulking character from the sci-fi movies, frozen in place. Its future is uncertain.

Proposals were made to extend the height of barriers along the staircases, but nothing was finalized. I find it difficult to imagine a better use for it, nor can I easily offer an opinion whether merely adjusting the height of the barriers would solve the problem. My initial reaction is that the “Vessel” is so imposing a presence that minor adjustments may have limited impact. However, after considerable community input and design review, the developer the Related Companies decided to re-open it with heightened security but not any raised heights to the barriers, but an admission fee of $10 was charged, and no one could enter alone.[11] Tragically, another suicide occurred after this re-opening in 2021, and the Vessel was closed again.[12]

It’s a bizarre experience to visit the Vessel. Tourists line up and enter in a loop into its interior while a stentorian guard barks orders announcing the limitations that they can only view up the vast staircases inside but cannot climb them. Once inside people gape upward at the stairs, and then continue their brief journey back outside.

The coarser annual flowers form a prelude to the Vessel, the climbing structure whose interior stairs have been closed to the public. Inside the hollow structure, visitors may only peer upwards, as all the stairs are blocked off.

Five images follow showing the sequence of arriving at the entrance of the Vessel, and exit:

Then, once inside, gaping up at the gigantic staircases and exiting unrewarded from a trip up to the viewing platforms.

The Vessel remains temporarily closed. Access to the ground-level base is free and open to the public Monday through Saturday 10am-8pm and Sunday 11am-7pm, with no reservation required. A determination for future access has not been made.

29. From the southern terminus of the High Line, it’s no more than a five minute walk across the West Side Highway along West 13th Street or West 14th Street to the understated, twin entrances to Little Island, the stunning new park which appears to float in the edge of the Hudson River. Little Island has attracted as much attention and is drawing as many visitors, even during the height of the pandemic, as the High Line. You can read my 3-part series: “A Leaf with Upturned Edges: Little Island by MNLA, Heatherwick Studio, Arup & others“; “…Part 2 of 3“; and “…Part 3 of 3.”

Little Island in July, 2022

Lighting overview of Little Island. Image: MNLA

30. The landscape architecture by MNLA for the Whitney Museum of American Art anchors the Gansevoort Street end of the High Line well into its setting on the building’s eastern and southern sides. The pavements and plantings introduce visitors to what to expect as they climb the stairs or take the elevators to the High Line. It is unfortunate that more space for pedestrians and landscape is not allotted along the museum’s West Side Highway frontage leading directly towards Little Island’s access points, but perhaps Renzo Piano, the architect, sought to thrust people directly into the industrial heart of the city. This neighborhood is called the “Meatpacking District,” and one can definitely feel squeezed tightly as the traffic rushes by pedestrians as they access one possible route to Little Island.

Exterior plantings at the Whitney Museum continue the same vocabulary as the High Line’s and disguise and embolden elevation changes. The street trees have been less successful.

31. The High Line continues its evolution. In revisiting almost ten years from my initial studies, I’m intrigued by the growth and resilience of the plant materials, but also by some signs of wear and tear. The pandemic has brought a much more restrained usage of the High Line that is often refreshing without long lines and crowding.

As the city emerges from the pandemic I wonder if enough energy will be generated in years to come to sustain the same level of use that kept millions of visitors coming to the park again and again. For all of its grace, beauty and diversity, the park is costly to build and expensive to maintain. With new extensions to the Moynihan Train Hall scheduled for completion this year and Hudson River Park likely to be constructed in the next few years, whether a multi-purpose, sustainable, and consistently affordable future on this iconic pedestrian parkway is achievable is hard to predict.

Following the examples set so far by the tenacity of New Yorkers, and as long as exuberance is tempered by restraint, I expect so.

Cumulative 2-part “High Line Redux 2023” Series End-notes

See High Line Redux 2023, Part 1 of 2 to see end-notes 1-5.

[6] See https://www.thehighline.org/art/projects/?type=billboard&pages_loaded=2

[7] See milelongopera.com. Also created by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the architect for the High Line (I did not attend the performance but it was reported to me by Cedric Tolley, a musician friend who lives in Chelsea).

[8] https://www.thehighline.org/art/projects/a-screen-test-for-an-adaptation-of-giselle/?utm_source=highline&utm_medium=art-homepage&utm_content=art&utm_campaign=art

[9] https://www.thehighline.org/blog/2021/01/11/a-vision-for-new-connections/ See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Line/Reconstructionand_Design

[10] https://www.thehighline.org/connections/

[11] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/26/nyregion/hudson-yards-vessel-reopening.html

[12] https://www.dezeen.com/2021/08/02/heatherwick-vessel-hudson-yards-suicide and https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jul/31/new-york-vessel-hudson-yards-death

Publisher’s Note:

See the High Line Project Profiles in the Greenroofs.com Projects Database for High Line, Phase 1; High Line, Phase 2; and High Line, Phase 3.

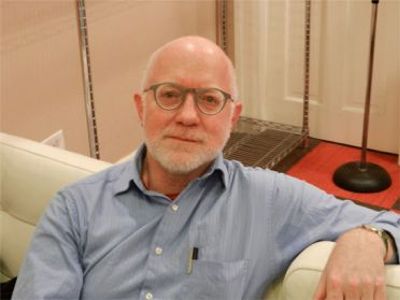

Steven L. Cantor, Landscape Architect

Photo by Thomas Riis

Steven L. Cantor is a registered Landscape Architect in New York and Georgia with a Master’s degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He first became interested in landscape architecture while earning a BA at Columbia College (NYC) as a music major. He was a professor at the School of Environmental Design, University of Georgia, Athens, teaching a range of courses in design and construction in both the undergraduate and graduate programs. During a period when he earned a Master’s Degree in Piano in accompanying, he was also a visiting professor at the College of Environmental Design at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He has also taught periodically at the New York Botanical Garden (Bronx) and was a visiting professor at Anhalt University, Bernberg, Germany.

He has worked for over four decades in private practice with firms in Atlanta, GA and New York City, NY, on a diverse range of private development and public works projects throughout the eastern United States: parks, streetscapes, historic preservation applications, residential estates, public housing, industrial parks, environmental impact assessment, parkways, cemeteries, roof gardens, institutions, playgrounds, and many others.

Steven has written widely about landscape architecture practice, including two books that survey projects: Innovative Design Solutions in Landscape Architecture and Contemporary Trends in Landscape Architecture (Van Nostrand Reinhold, John Wiley & Sons, 1997). His book Green Roofs in Sustainable Landscape Design (WW Norton, 2008), provides definitions of the types of green roofs and sustainable design, studies European models, and focuses on detailed case studies of diverse green roof projects throughout North America. In 2010 the green roofs book was one of thirty-five nominees for the 11th annual literature award by the international membership of The Council on Botanical & Horticultural Libraries for its “outstanding contribution to the literature of horticulture or botany.”

Steven’s most recent book is Professional and Practical Considerations for Landscape Design (Oxford University Press, 2020) where he explains the field of landscape architecture, outlining with authority how to turn drawings of designs into creative, purposeful, and striking landscapes and landforms in today’s world.

He has been a regular attendee and contributor at various ASLA, green roofs and other conferences in landscape architecture topics. In recent years Steven has had more time for music activities, as a solo pianist and accompanist.

Steven joined the Greenroofs.com editorial team in December, 2013 as the Landscape Editor. In February, 2015 he completed his 14-part series “A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective“and a survey of green roofs in Copenhagen Green Tour 2015.

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture